The Kilvenmani Massacre (1968)

Female Survivors – Historical Representation and Fictional Characters

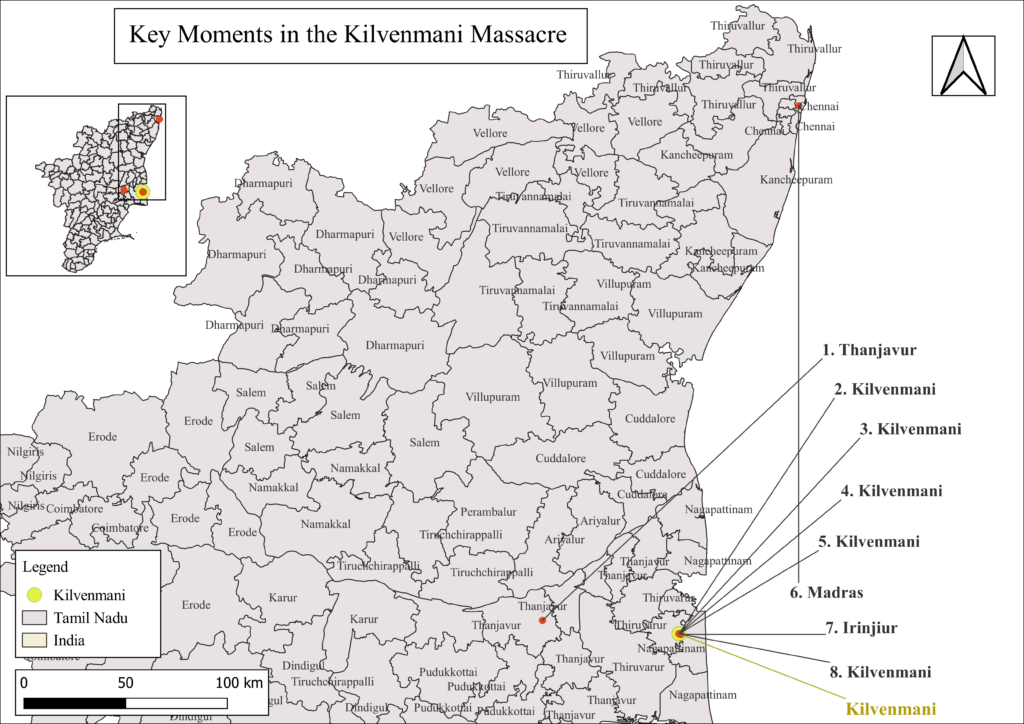

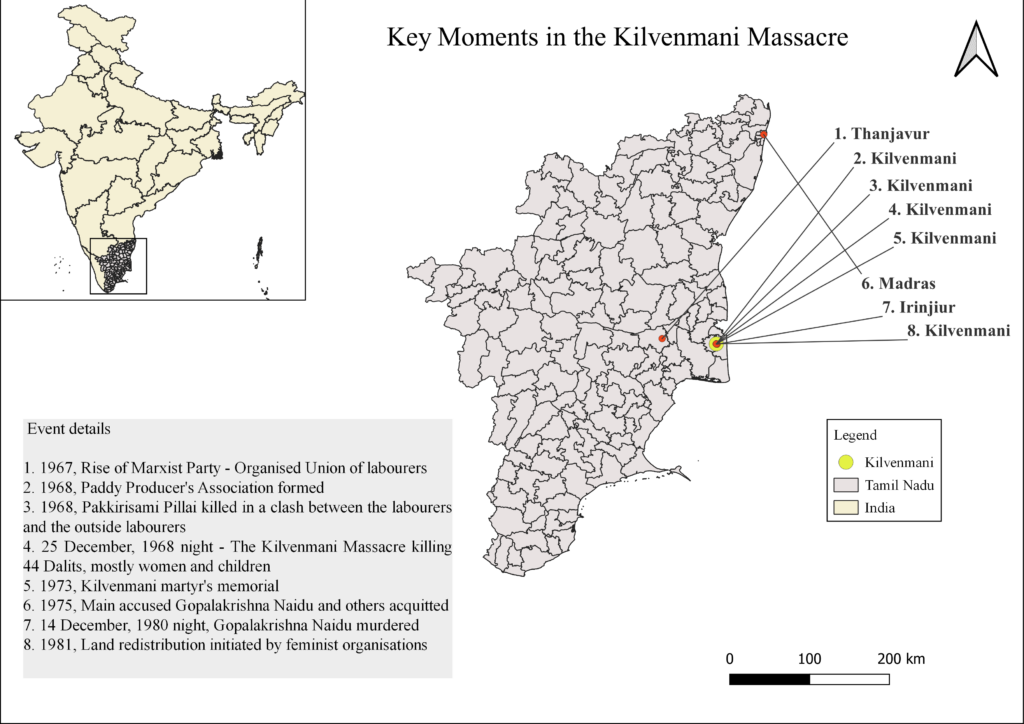

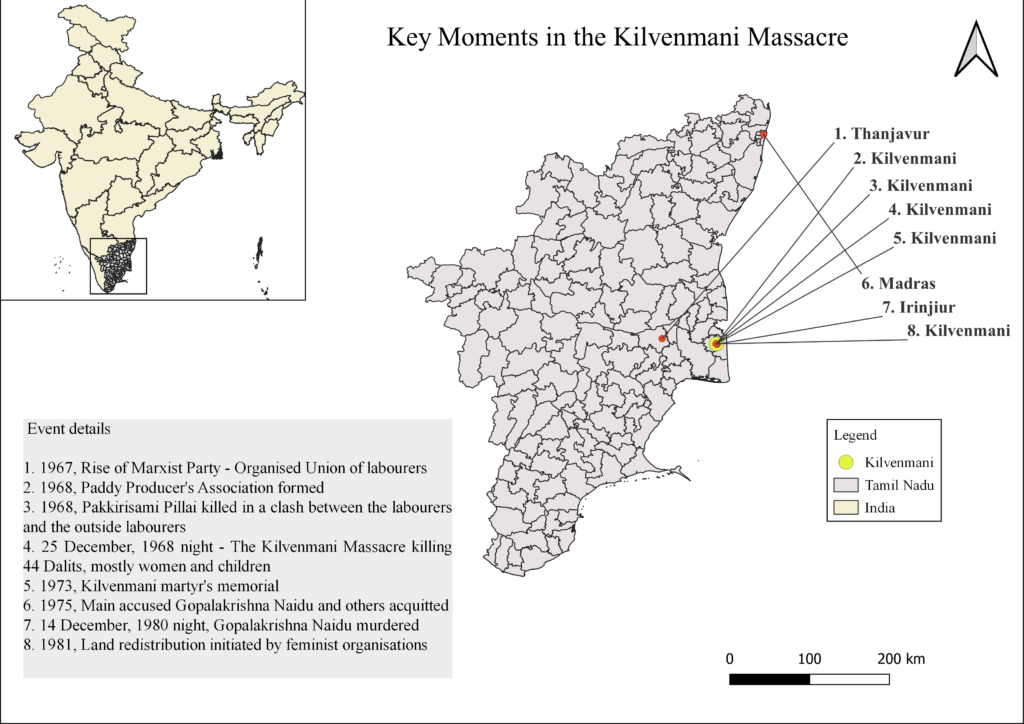

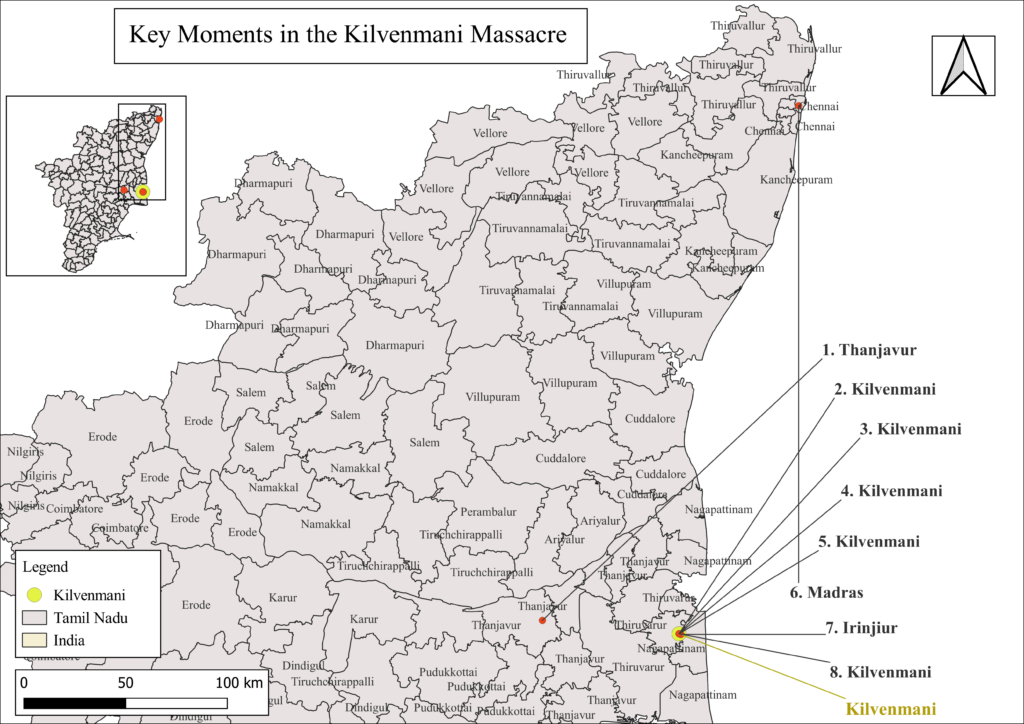

Key Moments in the Massacre

Background

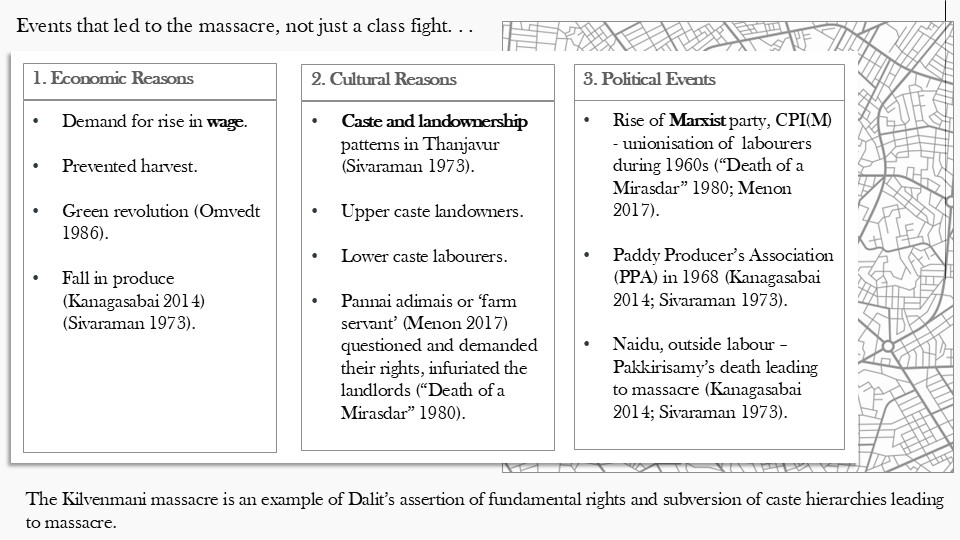

Kilvenmani/Keezhvenmani/Keezhavenmani Massacre (1968) took place in the Kilvenmani village, Thanjavur district of Tamil Nadu in 1968. On the night of 25 December 1968, 44 Dalits who took refuge in a hut, from the upper caste landlords and their henchmen who were setting fire to the village of Kilvenmani, were subjected to arson and died at the spot. Most of the deceased were women (18) and children (22) along with a few elderly people and men (2). This is the popular narrative while referring to the massacre which is often dismissed as a class fight between the landowning upper caste and the lower caste labourers. The latter protested for a hike in wages. However, there are economic, cultural, and political events, that took place over the years which eventually culminated in a massacre that is often hailed as ‘one of the earliest and most violent crimes in post-independence India’ against the Dalits.

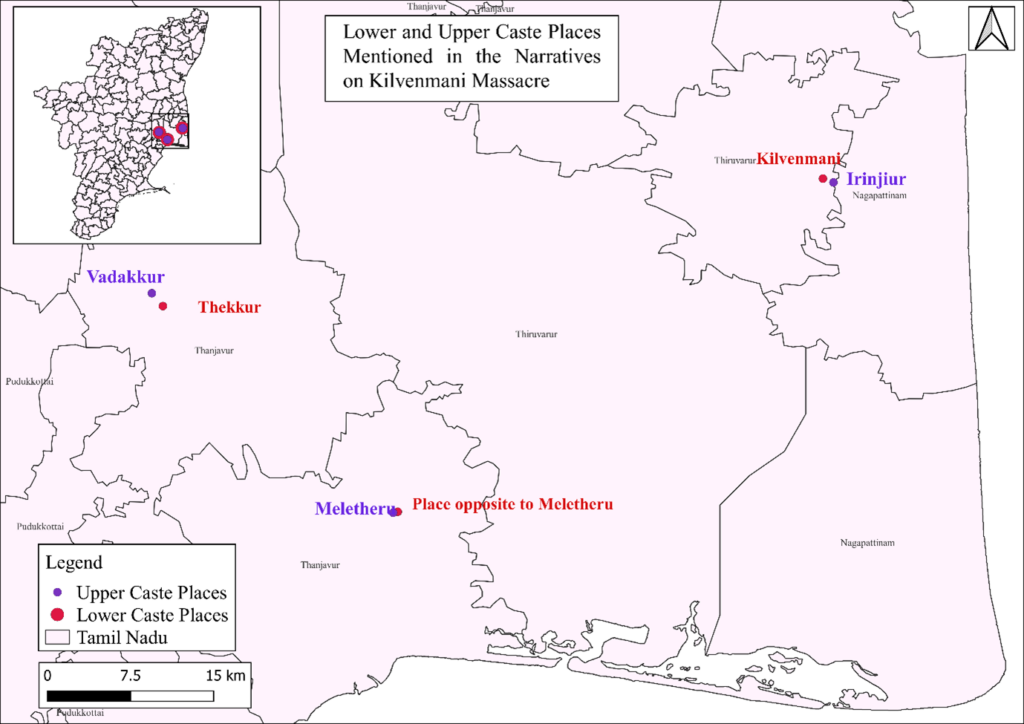

The caste-identity of the victims of the massacre was overlooked until recently both by the academia and mainstream media. The Kilvenmani massacre is often dismissed as a class conflict between the landlords and the labourers. Importantly, the labourers were all Dalits who were forced to work under the tyrannous upper caste landlords, who exploited them under the ‘Pannaiyal system’. ‘A pannaiyal (attached labourer) pledged the services of himself, his wife and their children to be born to the landlord until the loan, usually taken for marriage, of about Rs 50 was fully recovered’. Thus, the labourers were exploited economically and culturally based on their specific identities. The caste also determined the location of the Dalits in Tamil Nadu, as they were often relegated to the outskirts of the village, referred to as Cheri. Kilvenmani is one such ‘Harijan cheri’. This caste-based spatial segregation of the Dalits further rendered them more vulnerable to caste-based atrocities and violence.

“In fact, it was not just that the children were locked up in a hut and burnt to death, but there is one episode which anybody in Keezhvenmani will tell you again and again — how one of the mothers of a child in a desperate attempt to save the child threw the child outside, hoping that somebody will save the baby, somebody in the mob would have the humanity to save this child. But they basically chopped the baby into pieces and threw the baby back into the hut and set it on fire.

(Pawar 2018)

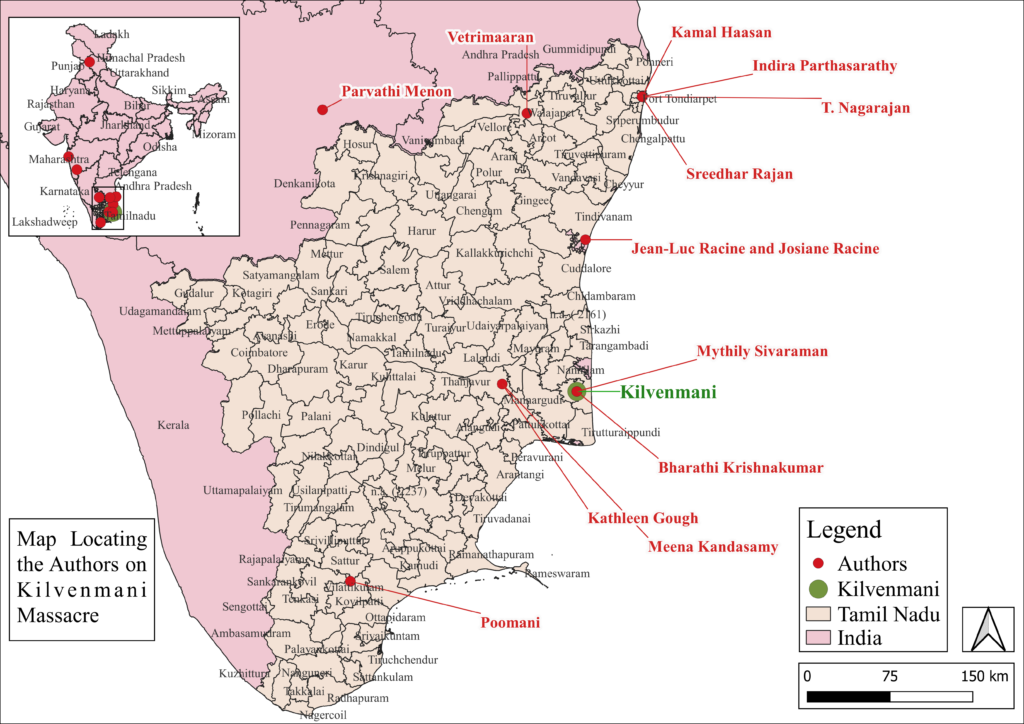

Mythily Sivaraman (1973), Kathleen Gough (1974), “Death of a Mirasdar” (1980), Gail Omvedt (1981), Jean-Luc Racine and Josiane Racine (1998), Hugo Gorringe (2006), Navneet Sharma and Pradeep Nair (2015), Parvathi Menon (2017) and Nithila Kanagasabai (2014) are some of the important research on the massacre. Kanagasabai (2014) underscores the possibilities in archiving the historiography of the women of the Kilvenmani massacre. Taking a cue from the works of Menon (2017) and Kanagasabai (2014), in this study we are attempting to fill the gap on the female narratives of the massacre. We are using a hybrid methodology that is a combination of digital cartography and feminist geocriticism. “The passage of time, lack of proper documentation and multiplicity of narratives have buried the incident in mystery and uncertainty” (Kanagasabai 2014), which highlights the importance of voicing the unheard narratives of the female survivors.

Sources Used for Mappings

Spatial Archive

Map Images

Analysis

- Historical and Fictional Representations

Number and Names: Fictional female characters that are identified in this study, are more in number (47) as compared to the data available on the historical representations (36 of 44). Names of the historical survivors are used repetitively in some of the fictional narrative. The fictional narratives are of significance to understanding the experiences of the upper caste women who were also silent perpetrators to the massacre (for instance, Naidu’s wife) as they were denied any agency due to their gender identity despite the caste privilege.

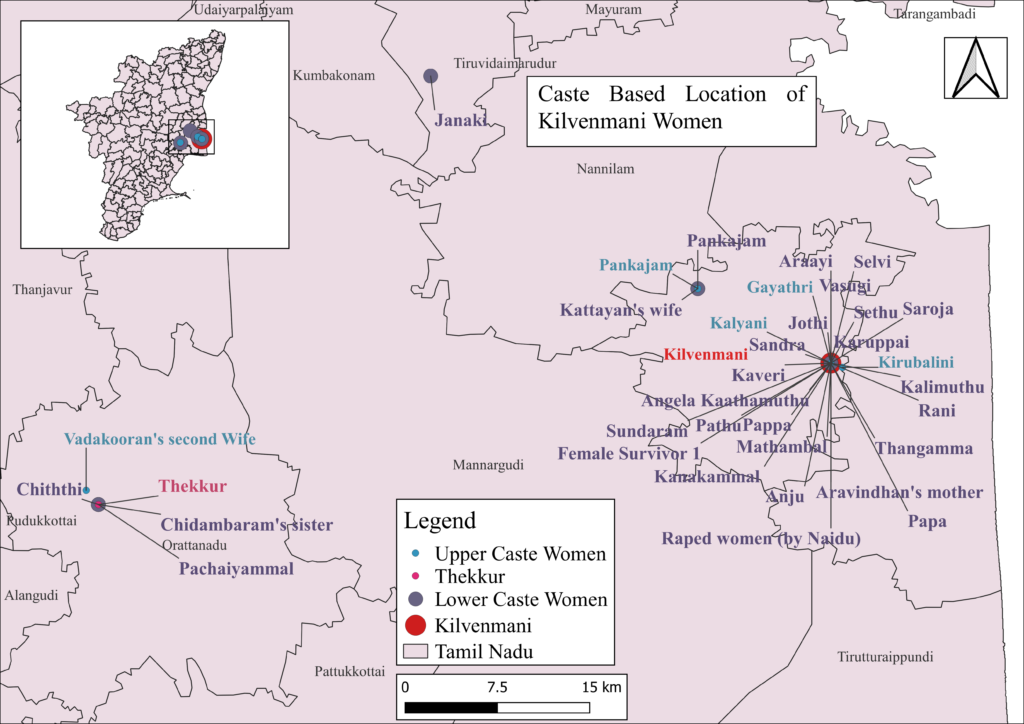

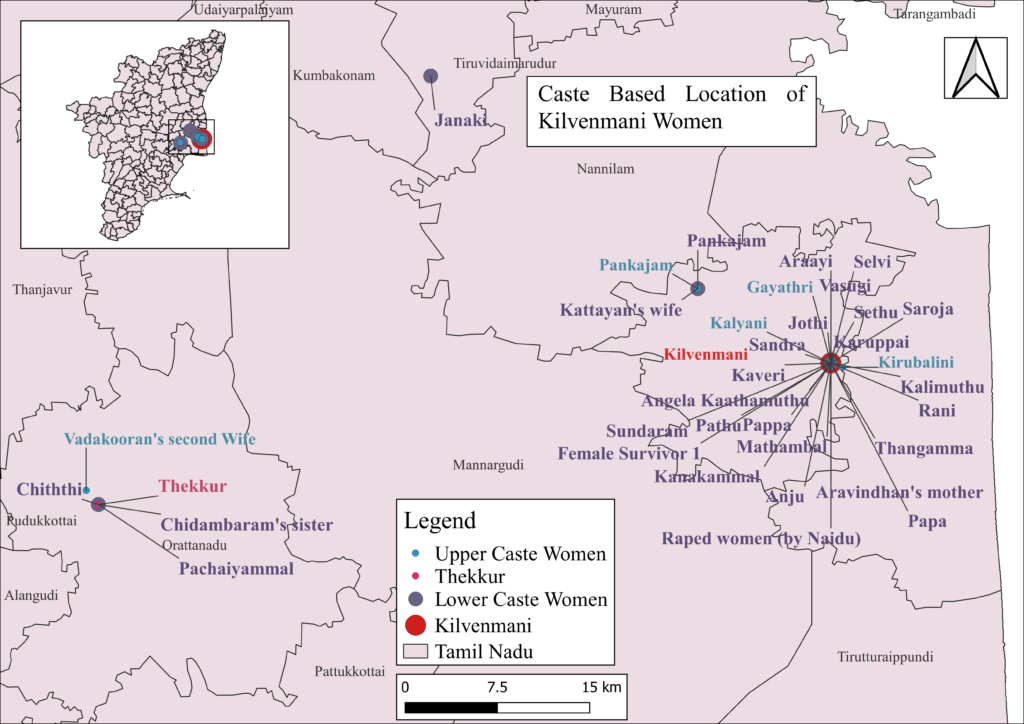

Location: caste identity determined the spatial location of survivors, usually situating the upper caste away from the Dalit Cheris, thereby protecting them from massacre and other caste-related atrocities. Figure (on the left) shows that both the lower caste and the upper caste women are placed in the same space – Thekkur – yet the advantage of the latter is the safety offered by their caste identity. This illustrates how women’s experiences of the same location can vary significantly based on their intersectional (caste and gender) identity, as analyzed through the lens of feminist geocritical theory.

The comprehensive examination of fictional and real/historical portrayals can be categorised into the following thematic areas (click to expand):

Intersectionality

Upper caste females and lower caste females experience of space and caste differs evidently in the narratives under consideration. Dalit feminist arguments rejecting homogenisation of lived experience of women into a monolithic category (Mohanty 2003) and adopting an intersectional approach that takes into account the gender, class, and caste differences is evident here. Women experienced spaces based on their caste and gender as seen here in the creation of upper caste female spaces and Dalit female spaces. Extending on Ambedkar’s concept of spatial hierarchy, here we can see the creation of gendered spaces of caste hierarchies. Corroborating the feminist geocritical proposition that space is multiple, shifting and characterised by differences in experiences especially based on the intersectional identity of the individual occupying the space, space should be considered as an intersectional category while analysing the female experiences of Dalit massacres in India..

Protagonists

The focus of the narratives is shifted to the male protagonists in the films, and his heroic actions as seen in Aravindhan (Aravindhan), Kann Sivanthal Mann Sivakum (Goutham)and Asuran (Sivasami). The act of placing a male protagonist, acting as a saviour is in stark contrast to reality as most of the ‘saviours’ associated with the massacre were feminist activists and organisations. The distortion of women’s heroic actions and redefining it as masculine actions is a result of ‘gendered heroism’ (Fried 1997) that refuses to acknowledge the leadership qualities of women. Patriarchal system with its traditional gender roles (of masculinity and femininity) expects only men and not women, to display valour and perform heroic deeds – as saviours or protectors of the marginalised. A re-gendering of the heroification discourse (Danilova and Ekaterina 2020) is required in the context of the Kilvenmani narratives as seen in Kandasamy’s work.

Real and Mythical survivors

Myths in India, have a built-in caste system (Kashyap 2023, p. 194) and have been traditionally used by the upper caste to propagate caste hierarchies. The narratives studied here, subverts this practice by using mythical characters to question the notions of spatial hierarchy and ‘purity-pollution’ concepts of the caste system. Kandasamy is known for offering “counter narratives of power and also to empower the female collective” by questioning the inherent caste and gender bias of myths (Kashyap 2023, p. 197).

Gender-based Violence

Rape is often used as a political weapon (Chakravarti 2018, p. 173) to silence the individual and the community. Dalit female body “is often used as a means for the upper castes to assert their dominant position over the lowest castes in the [caste] hierarchy” (Sabharwal 2015) which leads to an increase in gender-based violence during massacres. The gender-based violence that took place during the massacre are completely ignored in most of narratives despite the mention of rape in The Gypsy Goddess (pp 142) as well as in Ramayyahvin Kudisai. The focus of research and newspaper articles are solely on the burning of the hut, thereby overlooking other atrocities such as rape and police brutality that were committed as part of the massacre. There is also limited information on upper-caste female survivors who were present in or near the massacre site, both in historical records and fictional portrayals. This makes it difficult to understand their role in the incident. Were they also silent perpetrators or victims or both?

2. Space

The thematic findings on spatial elements are as follows (click to expand):

Creation of Gendered Spaces of Caste

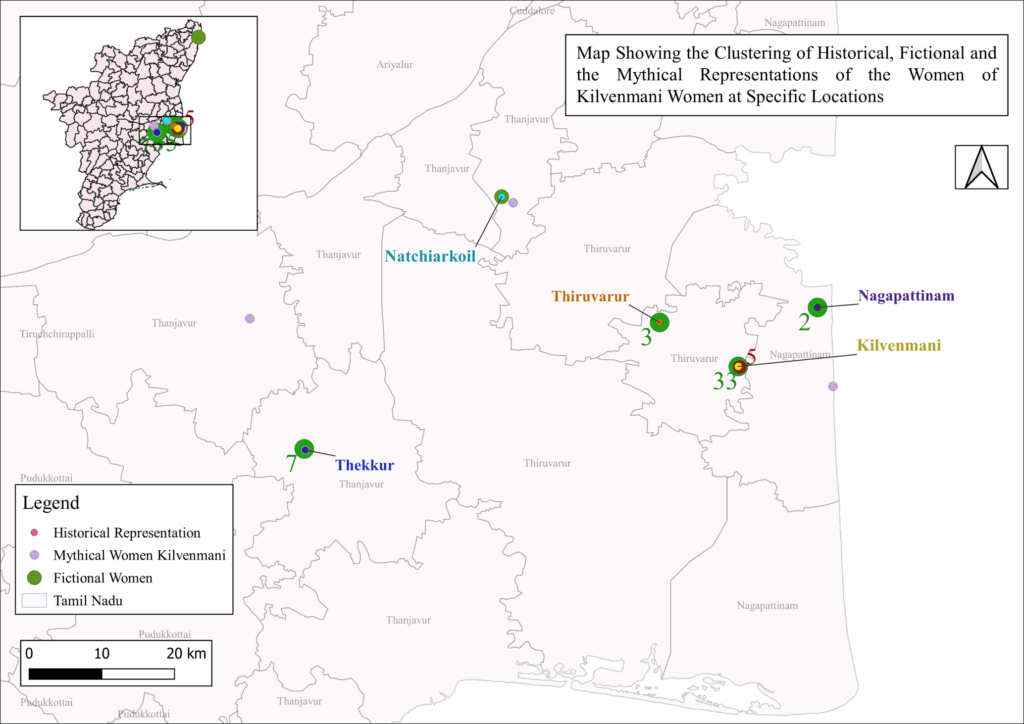

Figure above is compiled based on the clustering of survivors in specific places. The minimum value chosen for the curation of clusters is 2 and the maximum value is 33. The figures above indicates that the clustering of the survivors occur in five main geolocatable spaces – Kilvenmani (33 fictional and 5 historical representations), Nagapattinam (2 fictional representations), Thiruvarur (3 fictional representations), Natchiarkoil (1 fictional and 1 mythical representation), Thekkur (7 fictional representations), along with the fictional space of Satyapuri (which for the purpose of mapping is taken as Kilvenmani). The intersection between the real and the fictional survivors occurs mainly in the spaces of Kilvenmani and Satyapuri as the other fictional and the mythical characters are scattered. This shows a possible ‘third space’ where the real and the fictional survivors co-exist thereby indicating that the fictional narratives are based on the Kilvenmani massacre (even if it is not directly mentioned).

Real and Fictional Settings

The settings used in both the textual and visual fictional narratives are either real spaces that are geolocatable (using location coordinates) or fictional spaces both of which are closer to Kilvenmani, Nagapattinam, and Thanjavur. We found that the use of fictional settings enabled the writers to freely expand on reasons that led to the massacre and the events during the massacre while avoiding the socio-political implications that might arise on using the real names of the settings, victims and perpetrators. Fictional spaces and characters enabled the authors to talk about “the unspeakable and give voice to the unheard and unseen realities” (Müller 2018, p. 25) of the massacre.

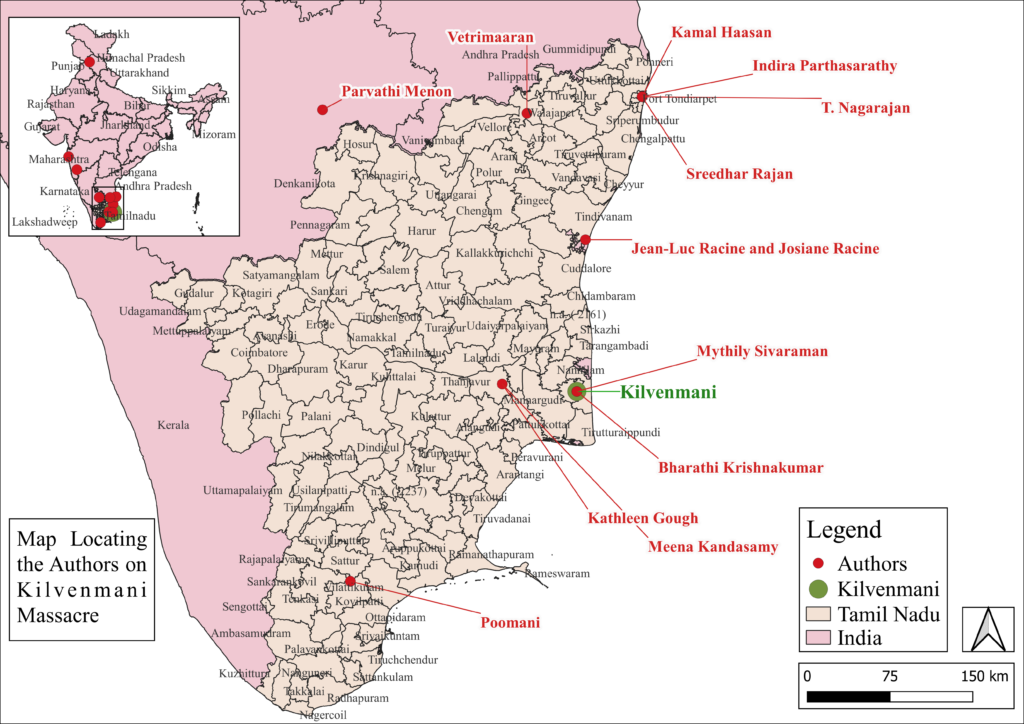

3. Additonal Literature

Authors – An analysis of the authors’ gender and spatial location helps reveal how these aspects influence the narratives within the primary fictional and non-fictional texts. Seven of nineteen authors who were considered for this study were women with the majority being males. Female authors (Kandasamy, Kanagasabai) are keener in uncovering the gaps in understanding the nuances of the Dalit female experiences whereas male authors were mainly focused on creating a heroic male protagonist (gendered heroism) who eventually became a saviour to the villagers/labourers. Female authors were able to utilise geography (both real and fictional) as a code to create female literary narratives in accordance with the geo-parler femme principle of feminist geocriticism. The female authors are also a mix of upper (Mythily Sivaraman) and lower caste (Meena Kandasamy) thereby highlighting the significance of allyship in Dalit feminist endeavours. Dalit female authors who were located closer to the site, leveraging their own lived experiences, were particularly adept at illustrating the intersection of gender and caste atrocities suffered by lower-caste women. Meena Kandasamy, a Dalit woman with her roots in Thanjavur, was able to gather more information from female survivors, as the survivors were more inclined to open up to someone, they felt was one of their own.

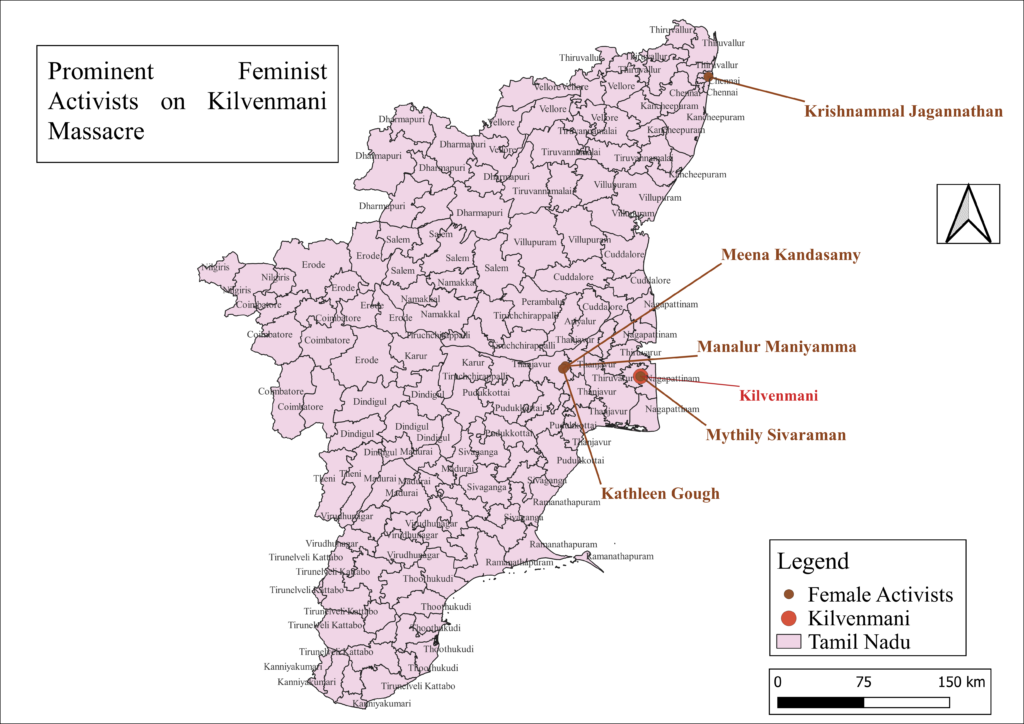

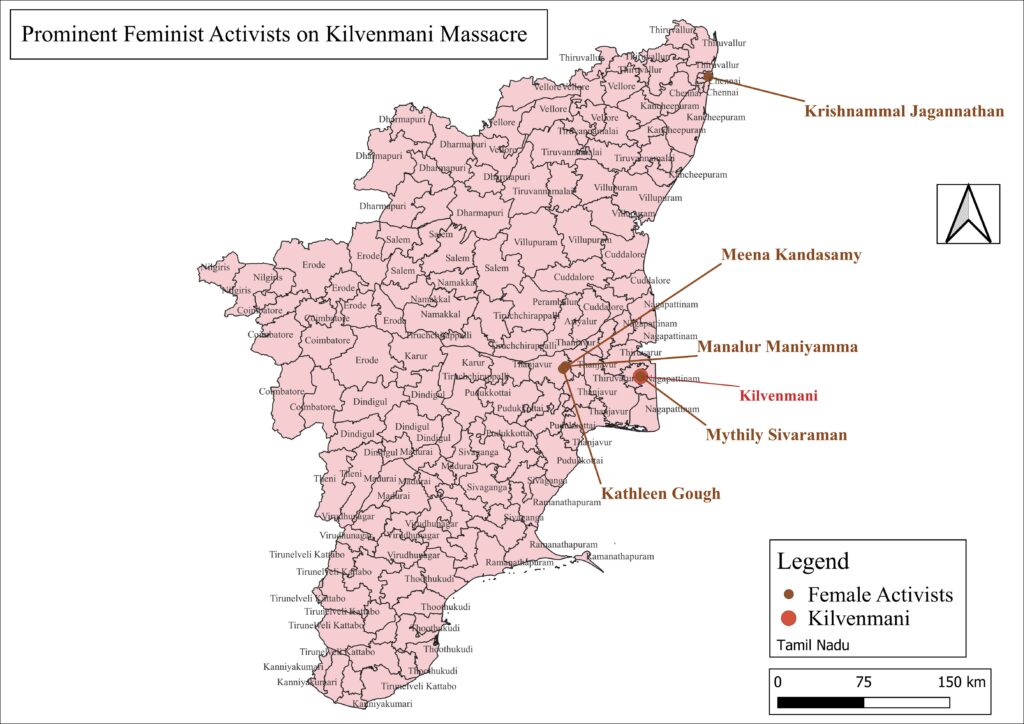

Feminist Activists and Organisations – Figure shows the names and locations of the activists. Some prominent figures include Krishnammal Jagannathan, Mythily Sivaraman, Meena Kandasamy and Kathleen Gough. Manalur Maniyamma was involved in the fight for Dalit land rights even before the massacre (Muralidharan 2018). Sivaraman was also part of the All India Democratic Women’s Association— the women’s wing of the CPI (M) (Thangavelu 2016). The activists belonged to different caste as Krishnammal, Maniyammal and Sivaraman are upper-caste women who broke away from the shackles of the caste to fight for the Dalit women. Their presence in rehabilitating the victims validates Rege’s (1998) argument to include Dalit feminist allies in the fight against gender and caste. The involvement of feminist activists and organizations underscores the need to integrate women into policy-making processes especially the ones related to land. They are better positioned to challenge and dismantle the creation and propagation of gendered spaces of caste that further leads to violence.

For more Analysis – Refer the Paper Digital Cartography and Feminist Geocriticism Case Study II: Kilvenmani Massacre

Conclusions

Fictional texts provide insights into subjective experiences while non-fictional texts help in setting the historical context and factual details. A combination of these sources enabled a multifocal feminist geo-centered exploration of differences in experiences of caste-based female geographies of the massacre. In order to conduct a comprehensive analysis of a massacre, it is important to look at the events before, during and after the massacre. The initial study began with identifying the cultural (caste), political (rise of CPIM), and economical (low wages) factors before the event that eventually led to the massacre. The events during the massacre consisted of arson, murder, and rape carried out by the upper caste landlord and his henchmen. The state, judiciary and the police force were silent perpetrators who facilitated the massacre. Following Fuchs (2020) concept, the survivors of the massacre continued fighting for their fundamental rights and this resulted in land redistribution after the massacre.

The participation of upper-caste feminist activists aligns with Rege (1998), Vandana (2021) and Paik’s (2017) argument for the inclusion of higher-caste perspectives in Dalit feminist theory, movements, and activism. The female experiences of the massacre – real, fiction, upper caste and lower caste are marked by a ‘politics of difference’ (Guru 1995). Dalit women experience the ‘triple burden’ (Chakravarti 2018) of caste, class, and gender during the massacres as opposed to the upper caste women who are protected from caste-based violence. Upper caste women, on the other hand, can become silent or active perpetrators of Dalit massacres as pointed out by Teltumbde (2010). Nevertheless, the upper caste female experiences of the massacre are not represented in the narratives thereby making it difficult to understand their role in the massacre. The differences in upper caste and Dalit female experiences sheds light on the intersectional identity of Dalit women that cannot be contained within the homogenous category of ‘women’. The real and fictional female survivors of the narratives also showed intersection of spatial experiences especially in terms of gender-based violence.

Most narratives also depict the creation of gendered spaces of caste (lower caste and upper caste female spaces) as a result of the spatial segregation in Tamil Nadu (at times using mythical female metaphors). Caste based spatial segregation resulting in spatial hierarchy (Ambedkar 1935) and geographical differentiation apartheid in south Indian villages are denoted here (Spate 1952). Caste, space and gender of the authors determined the portrayal of the female survivors in their writings.

Guru’s (2017) argument for lived experience as a pre-requisite to theorise on Dalits is evident here as Dalit female authors who resided closer to the site of the massacre were able to connect with and gather more survivor experiences as compared to others. Therefore, writers and researchers should strive for a Dalit feminitude (drawing from Punia’s 2023, concept of Dalitude) while analysing Dalit female experiences of massacres. Dalit feminitude refers to a new political movement and analytical device that uses a combination of lived experience and allyship to advance Dalit feminist and anti-caste movements and activism.

In India we can see that the caste identity (here Dalit) determines the geospatial location of the Dalit (concept of cheri or slum is an example for this) as a result of the socio-spatial segregation or spatial inequality inherent in the caste system (Patel 2022). Elimination of the caste-based spatial segregation in Indian villages, would prevent the large-scale caste-based, and gender-based violence against the Dalits. Dr Ambedkar had suggested that the Dalits and the marginalised communities should move to “cities and urban centres for livelihood as well as anonymity” (Patel 2022). However, this does not solve the problem as social reforms that eliminate caste in the rural India will be the only solution to reducing the number of Dalit massacres in India. One viable method to prevent Dalit massacres and other caste-based atrocities would be to eliminate the spatial segregation by mixing the population – Dalits and non-Dalits – thereby making it difficult to locate them in huge numbers. “The process of democratization requires alterations to social and well as political spaces and institutions” (Gorringe 2016). The state should therefore ensure the integration of the upper and the lower caste by enforcing strict laws that facilitate homeownership in prominent so-called upper caste areas by lower caste (Vakulabharanam and Motiram 2023). Creation of caste free public spaces can also help with the elimination of case based spatial segregation.

With respect to gender, women and their purity or honour preserved through endogamous marriages are seen as the vehicles of caste system (Chakravarti 2018). The state should promote exogamous marriage in an effort to slowly eliminate caste practices in India as opposed to endogamous marriages that are promoted by the caste system. Also, upper caste women can be active agents with a stake in preventing the massacres if empowered to rise above patriarchy. The patriarchal norms of the casteist Indian society generally forces upper caste women to act as silent (or at times as active) perpetrators in Dalit massacres (Teltumbde 2010). If upper caste women are not pressurised to adhere to the gender norms and caste rules then they might not be acting as perpetrators. Thus, eradication of space, gender and caste relation can result in the creation of a safer spaces for Dalits especially Dalit women.

Selected References

“Death of a Mirasdar.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 15, no. 51, 1980, pp. 2115–16. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4369342.

“Gentlemen Killers of Kilvenmani.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 8, no. 21, 1973, pp. 926–28. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4362661. Accessed 19 Feb. 2023.

Gough, Kathleen. “Peasant Resistance and Revolt in South India.” Pacific Affairs, vol. 41, no. 4, 1968, pp. 526–44. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2754563. Accessed 24 Feb. 2023.

Gough, Kathleen. “Indian Peasant Uprisings.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 9, no. 32/34, 1974, pp. 1391–412. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4363915. Accessed 22 Feb. 2023.

Gorringe, Hugo. “Out of the Cheris.” Space and Culture, vol. 19, no. 2, 2016, pp. 164–176., SAGE Journals, https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331215623216.

Gorringe, Hugo. “Which is Violence? Reflections on Collective Violence and Dalit Movements in South India”. Social Movement Studies, 5:2, 117-136, 2006. DOI:10.1080/14742830600807428

Kanagasabai, Nithila. “The Din of Silence – Reconstructing the Keezhvenmani Dalit Massacre of 1968.” SubVersions, vol. 2, Jan. 2014, pp. 105-130.

Menon, Parvathi. “Speaking Up: Voices from Agrarian Struggles in Thanjavur”. Review of Agrarian Studies, vol. 7(2), pages 84-90, July-December 2017.

Omvedt, Gail. “Capitalist Agriculture and Rural Classes in India.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 16, no. 52, 1981, pp. A140–59. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4370527.

Omvedt, Gail. “Thanjavur Studies.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 21, no. 50, 1986, pp. 2173–76. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4376439. Accessed 22 Feb. 2023.

Racine, Jean-Luc Racine and Josiane Racine. “Dalit Identities and the Dialectics of Oppression and Emancipation in a Changing India: The Tamil Case and Beyond”. Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 1 May 1998; 18 (1): 5–20. doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/1089201X-18-1-5

Sharma, Navneet and P. Nair. “Kilvenmani to Javkheda: An Antithesis to Ambedkar’s Nation”. Mainstream, VOL LIII , No 38, New Delhi, September 12, 2015. http://www.mainstreamweekly.net/article5920.html

Sivaraman, Mythily. “Gentlemen Killers of Kilvenmani.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 8, no. 21, 1973, pp. 926–28. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4362661.

The Land Ceiling Act. PRS Legislative Research (PRS), Act (58/61, Tamil Nadu, 1961.

The Tamil Nadu Cultivating Tenants Protection Act. PRS Legislative Research (PRS), Act (25), Tamil Nadu, 1955.

The Tanjore Pannaiyal Protection Act. PRS Legislative Research (PRS), Act (14), Tamil Nadu, 25 Dec. 1952.

Yadav, Kanak. “Gentlemen Killers: The Politics of Remembering in Meena Kandasamy’s The Gypsy Goddess.” Contemporary Voice of Dalit, vol. 9, no. 1, May 2017, pp. 113–20. SAGE Journals, https://doi.org/10.1177/2455328X17691163.