The Marichjhapi Massacre (1979)

Female Survivors – Historical Representation and Fictional Characters

Timeline of the Massacre

Background

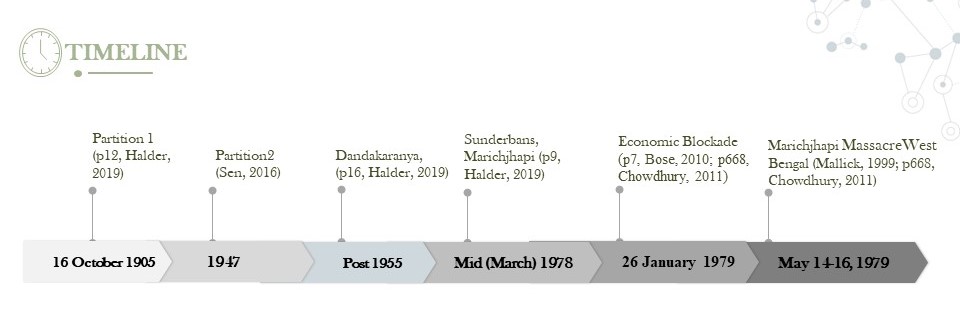

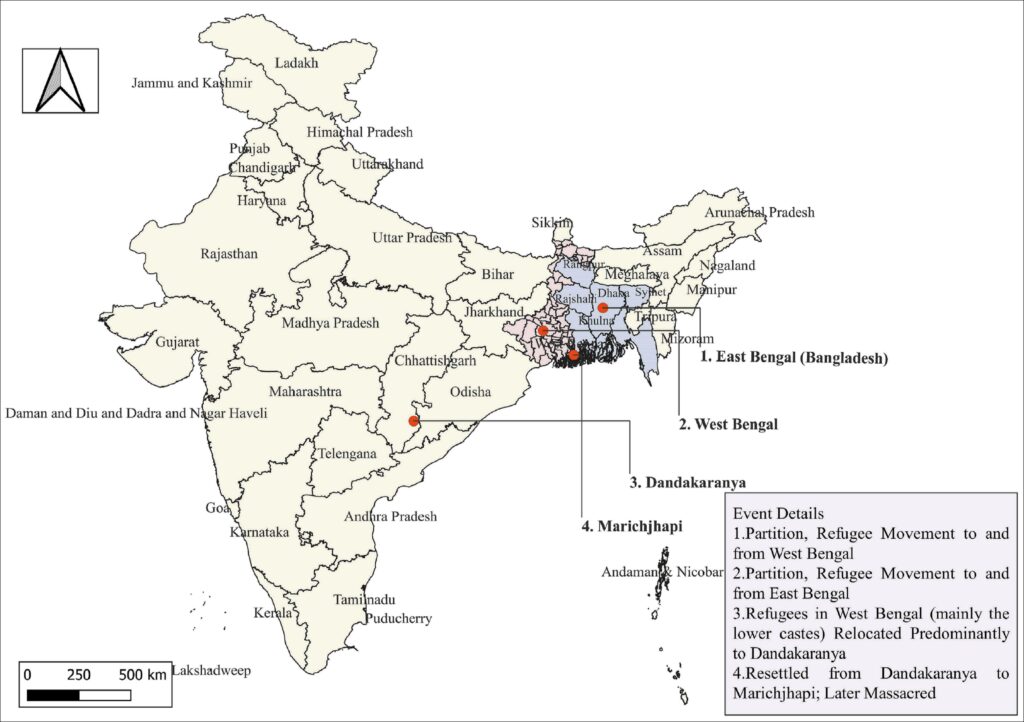

The Marichjhapi massacre (aka Morichjhapi/Marichjhanpi) took place in West Bengal in 1979. The Bengali Hindu Dalit refugees from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) who settled in Marichjhapi island of Sunderbans during partition of India, were forcefully evicted from the island from May 14-16, 1979, by the police under the left government. The earlier attempts to rehabilitate the refugees in Dandakaranya (in then Madhya Pradesh now Chhattisgarh) by the government of India failed, because it was a semi-arid land and the “area was entirely and culturally different from that of the refugees”. Though initially “the left-dominated opposition took up the case of the refugees”, upon gaining power the Communist government saw them as a “liability” and cited different reasons, from caste to ecological conservation, as the reasons for their eviction.

The massacre, often compared to Jallianwallabagh, the largest massacre in India began with an economic blockade to the island on 26 January 1979 to dislocate the refugees which further led to police firings, both together, resulting in the death of 663 people. Women refugee settlers were raped, tortured, and killed. The actual fatality of the event is still unknown with an estimate ranging from 10-10,000 as at least “4000 families were massacred in their fight against the state”. The reason for the ambiguity in death count is the ban on media coverage of the massacre and the reluctance of the state to accept that the massacre had happened. The central government’s Scheduled Castes and Tribes Commission, for instance, denied the massacre despite possessing prior knowledge about the same. This could also be a reason for the general lack of public discussions on the incident.

Map Shows the Key Moments in the Massacre

It is impossible to provide any documentary evidence to prove that institutional casteism might have worked behind the Left Front policy in Marichjhanpi. We can only pose a counter-factual question: if the settlers were Banerjees, Mukherjees, Boses, Mitras, Senguptas, and Dasguptas or in other words, if they belonged to the three traditional higher castes of Bengal who mostly constituted the elite ‘bhadralok’ [upper-caste], would the responses of the government and the civil society be the same? The answer, we think, should be an emphatic no. And there lies the caste factor, which should impel the ‘savarna bhadralok’ to introspect about their latent casteism that remains deeply embedded in their overtly elitist culture.

Bandyopadhyay and Chaudhury, Caste and Partition in Bengal.

The caste identity of the refugees who settled in Marichjhapi also played a significant role in their settlement in Marichjhapi, eviction and their subsequent massacre. The first two waves of refugees from East Pakistan “constituted mainly of the urban middle class and professionals, and rural middle class,” who “with the help of their friends, relatives, caste members and other influential social networks, found a foothold in West Bengal, particularly in Calcutta” (Chakrabarti 1990 cited in Chowdhury 2011; Mallick 1993, p. 24, 129, Sen 2015). This caste based spatial access of the refugees is also pointed out by Anowar (2021) “the upper caste refugees who came earlier settled in Calcutta and its suburbs. They occupied government land, offices, and houses, and transformed them into Jabardakhal (squatter) colony” (4).

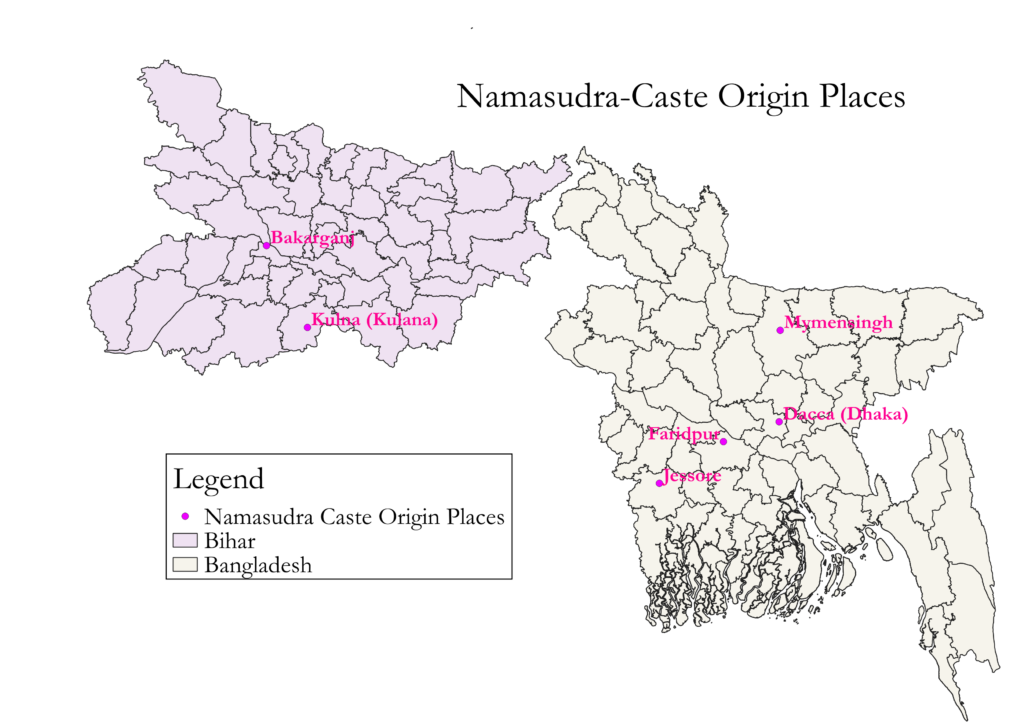

Sengupta (2011) and Anowar (2021) also shed light on this caste-privilege. The last wave of refugees belonged to different castes like “Namsudra, Paundra, and Rajbansi, and some adivasis like Santhals” (Bandyopadhyay and Chaudhury 2022, p. 6) and sub-castes within the Bengali lower castes, such as “Chanrals, Bagdis, Mochis, Bauris, Malos, Jeles, Dhobis, Doms, Kaibartyas and so on” (Anowar 2021, p. 3) commonly referred to as ‘Dalits’. Chowdhury (2011, p. 667) identifies the majority of the Marichjapi refugee settlers as belonging to the untouchable caste of ‘Namasudras’.

Sudras are the lowest in the caste hierarchy, after Brahmins (priests), Kshatriyas (warriors) and Vaishyas (Merchants) (Chowdhury 2011) and Namasudras are a sub-caste within the Sudra caste. They are an industrious agrarian community with artisan skills. They were a hard-working agrarian community with artisan skills, belonging to a sub-caste within the larger Sudra caste – Sudra being the lowest caste in the Hierarchy after Brahmins (priests), Kshatriyas (warriors) and Vaishyas (Merchants). The first two waves of refugees from East Pakistan “constituted mainly of the urban middle class and professionals, and rural middle class,” who “with the help of their friends, relatives, caste members and other influential social networks, found a foothold in West Bengal, particularly in Calcutta”.

The Namsudras were the last of the refugees to move to West Bengal due to their poor socio-economic conditions. Unlike the previous refugees, lacking “family and caste connections”, they had to “solely depend on the government for their survival”. Thus, their caste-identity denied them access to prominent areas of West Bengal like Calcutta, thereby forcing them to re-locate to Dandakaranya and later to Marichjhapi, the latter whence they were forcefully and violently removed (refer figure above).

The victims’ identities as Dalits and refugees worked against them. The Marichjhapi massacre is an example of Dalit claim for land ownership and subversion of caste hierarchies which eventually led to a massacre.

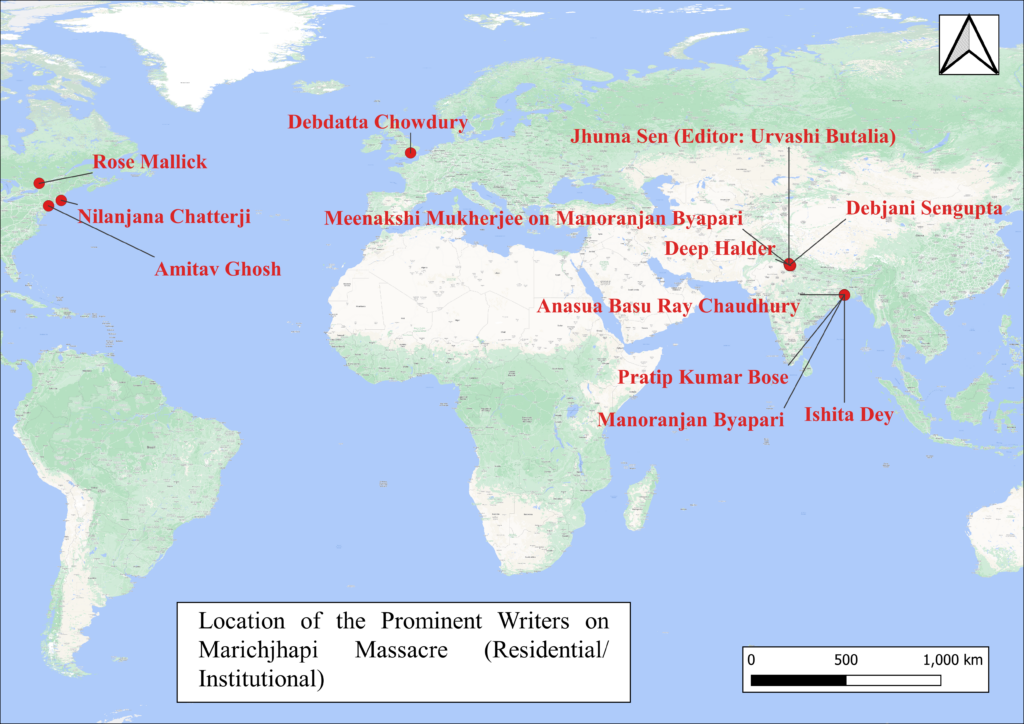

Nilanjana Chatterjee (1992), Rose Mallick (1999), Annu Jalais (2005), Meenakshi Mukherjee (2007), Manoranjan Byapari, Pradip Kumar Bose (2010), and Debdatta Chowdhury (2011) are some of the prominent writers and researchers on the Marichjhapi massacre.

Sources Used For Mappings

Spatial Archive

Map Images

Analysis

1. Historical and Fictional Representations

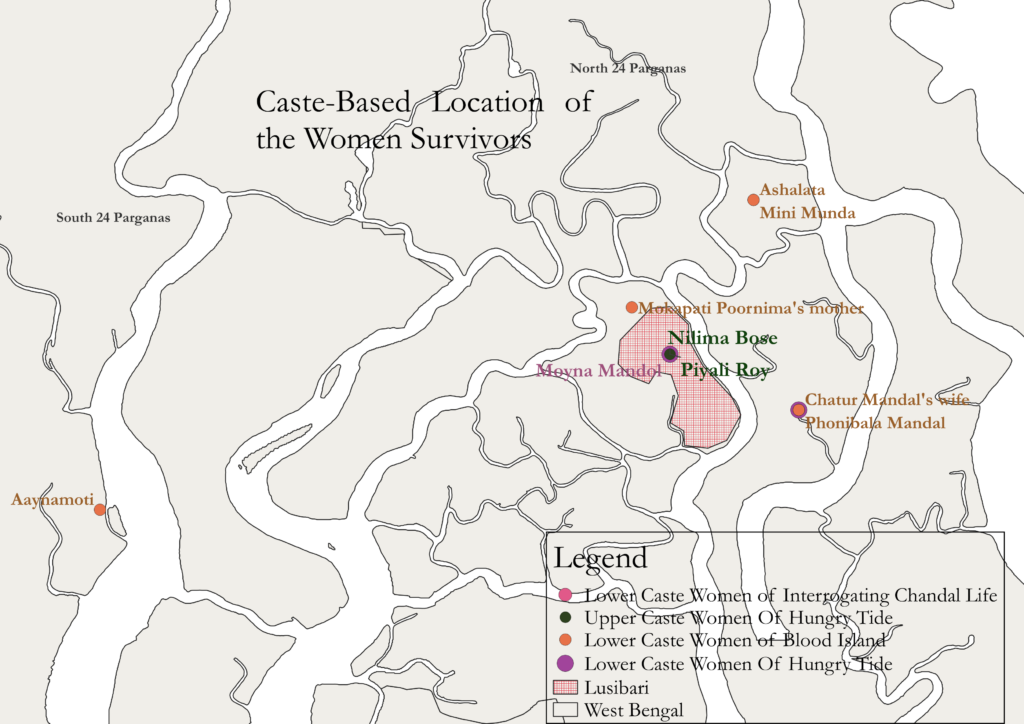

It was difficult to identify the names of the real survivors as most survivors were denoted as some man’s daughter, wife, sister etc., in the materials that were consulted for this study. In Blood Island there are multiple instances where this anonymity of the female survivors and the reasons for it are mentioned like, “Paunder’s sister has become her only identity”, “no one really knew her name or bothered to ask about it after she became Chatur Mandal’s wife” (p 40, 70, Halder, 2019). Also, the latest location of many of the survivors are unknown. Some of the real survivors are in Kumirmari, Satjelia and Gosaba, (P2458, Jalais, 2005),three islands that are close to Marichjhapi. Post massacre the female survivors are still located close to the site of the massacre indicating that they are still not rehabilitated or compensated for their loss. They still live in close vicinity to the space where they had to endure the trauma of a lifetime.

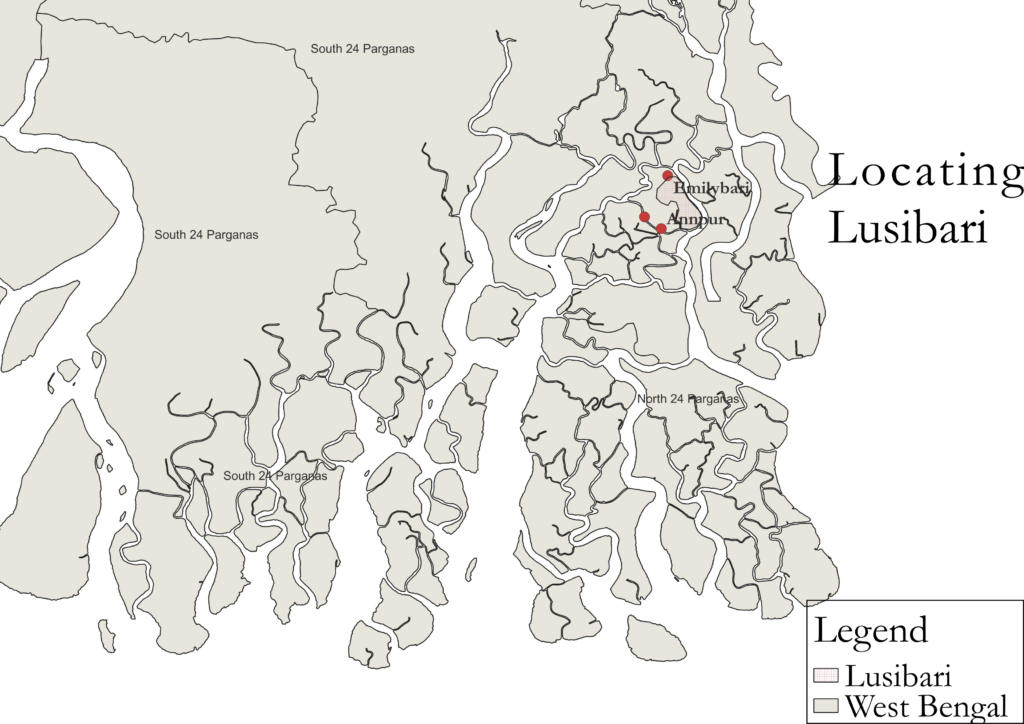

Identifying the fictional survivors, on the other hand, was relatively easier but locating them in real places was difficult as most of them were in the fictional space of Lusibari. It was found that while the real survivors were scattered in the states of West Bengal, Orissa and Chattisgarh, the fictional women were mostly confined to the Sundarbans especially Lusibari and Marichjhapi, thereby narrowing the narrative of fictional representation of Dalit female experiences to one space alone. Consequently, the intersection between the real and the fictional survivors occurs mainly in the space of Sundarbans, specifically near Marichjhapi, Satjelia, Gosaba, Kumirmari and Hamilton islands. The intersection of the real and the fictional female survivors also lead to the presence of a possible ‘third space’ where a hybrid of the real and the fictional spaces (and survivors) coexists.

2. Space

The caste-based location and resettlement of the refugees from East Bengal is explicit in the narratives examined for this study. A striking contrast is observed between Kolkata and Marichjhapi where the former is seen as the home for upper caste refugees who were welcomed by their relatives and other connections while the latter were occupied by the lower caste refugees who did not have any acquaintance in the capital city (Prafulla K., Cited in Chowdhury, 2011). However, the conditions of the female refugees (of both upper and the lower caste) in these spaces are largely left unexplored even in the papers that attempted a study of the spatiality of the massacre. This negligence of the female refugee experiences in general is addressed by Bose as pointed out in page 10 of this study. Even post the massacre Dalit refugee women are still in the outskirts; denied access to the capital city; and are still segregated based on their caste identity (figure 10).

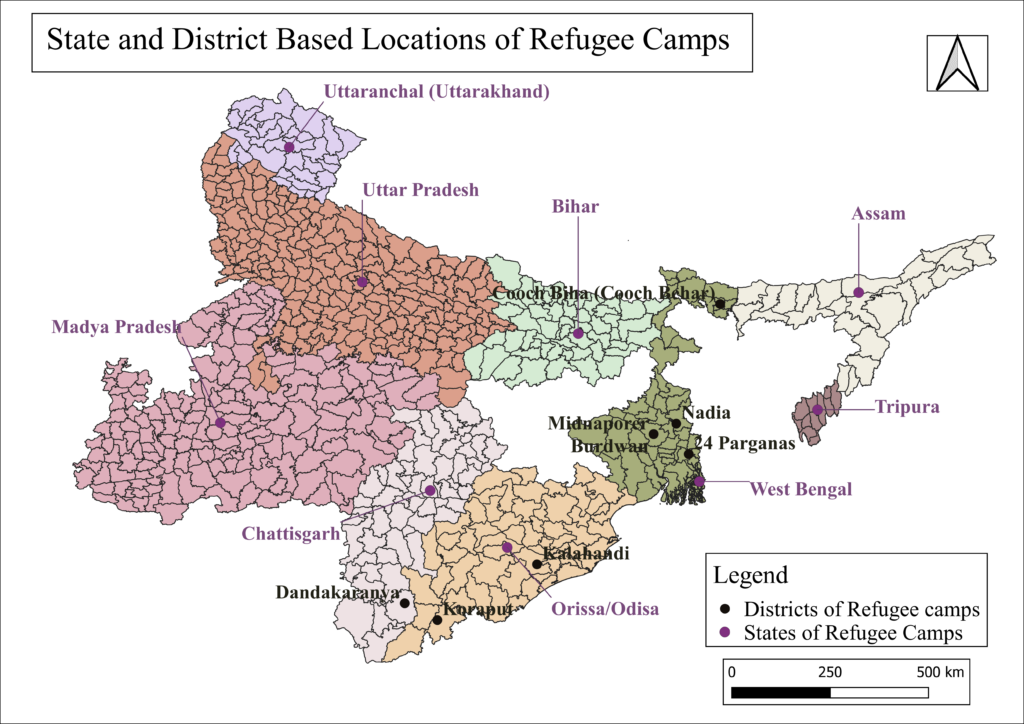

The refugee camps were predominantly located in the states of Chattisgarh, Uttar Pradesh, Uttaranchal, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal, Orissa and Jharkhand. These spaces were specifically chosen for camps mainly because of their proximity to the original place of the refugees (East Bengal). The materials considered for this study identifies the origin states of the Namasudra caste (of refugees) as Bihar and Bangladesh. Thus, the proximity of their original land to Marichjhapi and the Sundarbans prompted the refugees to relocate and settle there as it meant that they would experience similar socio-cultural habits, geography and climate. The flow map of the refugee movement shows that the main spaces occupied by the refugees during their migration from East Bangladesh to India are Hasnabad, Marichjhapi and Dandakaranya (based on the frequency of the places mentioned in the sources considered for this study). The places also served as a location for prominent refugee camps. The study aims to obtain the female experiences in these spaces in future through interviews of survivors.

From the available data visualization, it is easy to conclude that first the fictional representation of the women is lesser than the real women. Second, the lower caste women who were affected by the massacre are more largely represented and they were located close to the site of the massacre as compared to the upper caste women (less data is available on the upper caste women both in fictional and non-fictional works) who occupied comparatively safer geographical location. This also elucidates the caste-based geographical division of spaces in West Bengal which in turn led to caste-based massacres (using arson and police firing) thereby rendering lower caste women more vulnerable. It is difficult to obtain data on upper caste survivors (if any) compared to the lower caste ones. Thereby revealing the importance of caste in the massacre. The women of the massacres were exploited based on their socio-political, cultural identity and caste-based physical location as evident from the results and analyses of the narratives presented above. This relation between the spatial location of the survivors and the intensity of exploitation suggests that space should be considered as a category in the intersectional identity of the Dalit women as the caste-based geographical location and vulnerability of Dalit female exploitation are directly proportional.

3. Authors

The authors of the primary fictional, non-fictional and research materials studied here are also predominantly males. Thirteen authors were considered for the location-based database creation (figure 11), of which five were women. The gender of the writers and their spatial location also play an important role in ensuring the visibility of Dalit refugee female experiences of the Marichjhapi massacre. It is interesting to see that the writers are located across the world though the majority are located in India, especially in Bengal. Lack of female writers could be a reason for the absence of female narratives on the massacre. It is also evident that the existing female writers are mostly upper caste thereby highlighting the dire need for more Dalit female writers with first-hand experience of discrimination to conduct study on the female narratives as well.

For more Analysis – Refer the Paper Digital Cartography and Feminist Geocriticism: A Case Study of the Marichjhapi Massacre

Conclusions

The feminist geocritical and digital cartographical reading of Marichjhapi massacre based on the selected texts reveal that the place Marichjhapi, and the female survivors still bear the trauma of the massacre. The conditions of the female survivors have not improved post the massacre, with most of them living near the site of the massacre, awaiting compensation and rehabilitation. The land and gender i.e., female, connections are evident in real and fictional narratives as mostly female survivors connect the space of Marichjhapi to the trauma of the massacre (ex: Kusum and Mana). The fictional narratives on Marichjhapi (in English) are less in number and even the one studied here makes use of a fictional space as its central setting. The fact that the state is denying the occurrence of the massacre gives a fictional facet to the event itself. This points to the alarming need for narratives (both fictional and non-fictional) on Dalit massacres that document and explore the spatial relation of caste and gender in such massacres. The overall study suggests that the hypothesis of a possible relation between caste, gender and the spatial location of Dalit women is true. The caste identity (of being a Dalit) determines the spatial location of the female survivors which in turn render them more susceptible to gender and caste-based violence during the massacres. The anonymity of the female survivors in most non-fictional narratives also highlights the importance of this study that aims to render the Dalit female survivors visible in the spaces that they occupy.

References

Bose, Pradip Kumar. “Refugee, Memory and the State: A Review of Research in Refugee Studies”, Refugee Watch, no. 36, December 2010.

Chatterjee, Nilanjana. Midnight’s Unwanted Children: East Bengali Refugees and the Politics of Rehabilitation. Brown University, May 1992. PhD Thesis.

Chowdhury, Debdatta. “Space, Identity, Territory: Marichjhapi Massacre, 1979.” The International Journal of Human Rights, vol. 15, no. 5, 2011, pp. 664–682., https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2011.569333.

Elahi, K. Maudood. “Refugees in Dandakaranya.” International Migration Review, vol. 15, no. 1/2, 1981, p. 219., https://doi.org/10.2307/2545338.

Jalais, Annu. “Massacre’ in Morichjhapi.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 40, no. 25, 18-24 June, 2005, pp. 2458-2636. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4416755

Kandasamy, Meena. The Gypsy Goddess. 4th Estate, 2016.

Mallick, Ross. “Refugee Resettlement in Forest Reserves: West Bengal Policy Reversal and the Marichjhapi Massacre.” The Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 58, no. 1, 1999, pp. 104–125., https://doi.org/10.2307/2658391.

Mukherjee, Meenakshi. “Is there Dalit writing in Bangla?”. Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 42, no. 41, 13 October, 2007. JSTOR, https://www.epw.in/journal/2007/41/perspectives/there-dalit-writing-bangla.html?0=ip_login_no_cache%3D40a2072a79e3f03c5e9000873f86102a